Patricio Bustamante D. bys.con@gmail.com Archaeoastronomy Researcher, Taller Taucan, Fellow researcher of The Los Alamos National Laboratory Geographic Information Systems for the Preservation of Archaeological Sites and Petroglyphs. Member of AURA, the Australian Rock Art Research Association. W. Fay Yao. fyaogm@gmail.com IEEE Computer Society, IEEE Nuclear and Plasma Sciences Society, Resource and Information Specialist, Albuquerque Public Schools System,. Daniela Bustamante. danaluvskurt@yahoo.co.uk Architecture graduated.

Abstract

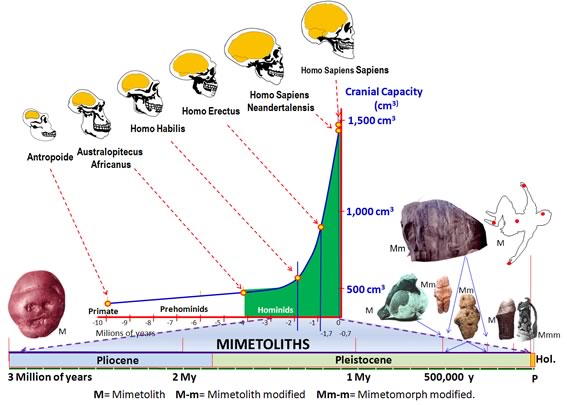

Bednarik (2009) described the Makapansgat jasperite cobble, a stone shaped as a human face deposited 2.5 to 3 million years ago. Tsao et al. (2006) demonstrated that face perception is a crucial skill to primates, humans and macaque monkeys. Applying two methodological tools of the Entorno Archaeology - Psychological and Geographical Entorno-, may allow to understand the process that probably led the Pleistocene humans to sacralize rocks -Mimetoliths- and objects -Mimetomorphs- with natural forms that resembled animals or human beings, in increasing scale, from small rocks, big rocks, mountains and Mountainous ranges, in the early Chinese culture, where we have found that three mythological characters: Pan-Gu (盘古), Fu-Xi (伏羲) and Shen-Nong (神农), probably were sacralized mountains. Mimesis, by the psychological phenomena of Pareidolia, Apophenia and Hierophany (The PAH triad), might explain the many instances when humans between Pleistocene and early chinese culture attributed religious significance or extraordinary connections to ordinary imagery and subjects. On the other hand, Mimetoliths and Mimetomorphs might contribute to explain the origins of Palaeoart, animism and religion. Key

words: Palaeoart, Mimesis, Pareidolia, Apophenia,

Hierophany.

1.

Introduction:

This article is the result of the research in archaeological sites of Chile and other countries in America. In previous papers PAH triad was proposed as an ubiquitous phenomena. The first version of this paper was presented in the IFRAO 2010 Congress, Foix - France, 'Pleistocene Art of the World'. Symposium. SIGNS, SYMBOLS, MYTH, IDEOLOGY. Pleistocene Art: the archeological material and its anthropological meanings. To understand the phenomena and processes that took place during the Pleistocene era, we must open up our perspective in order to acknowledge what happened before and after. This

paper analyzes the influence of three psychological phenomena inherent to all

human beings: Pareidolia, Apophenia and Hierophany (PAH Triad), (Bustamante

2008) in the recognition of Mimetoliths and Mimetomorphs, in the period between

3 millions in the past and the formative period of the Chinese culture. Also examines modern cases.

The

PAH triad does not explain ‘spiritual’ matters, but digs into the formulation

of images by means of our senses. While studying objects, geographic features,

sounds and signs in the surroundings of a specific area, it comes useful to

inquire ourselves What does it look like? In this article we will only study

visual phenomenon.

2.

Concept Definitions:

Pareidolia (psychological

phenomenon): involving a vague and random stimulus (often an image or sound)

being perceived as significant. Psychological phenomenon related to the

Rorschach test.

PAH Triad (psychological phenomenona): Pareidolia-Apophenia-Hierophany working simultaneously, is changeable among diverse individuals. The PAH triad is part of the unconscious mechanisms inherent to every human being, present in the primary stages of the early development of the human conscience. Mimetolith

(M): 1.a. a natural topographic feature or rock which natural shape resembles something else –

human, animal, plant, manufactured item, or part(s) thereof. (Dietrich 1989).

Mimetomorph

(Mm): Any kind of material (bones, wood, mud and others)

with natural shapes that resembled animals, human beings or other objects. Many

of these material don’t survive passage of the time.

Mimetolith

Modified (M-m): Natural shape altered by

human beings.

Mimetomorph

Modified (Mm-m): Natural shape altered by

human beings.

Entorno’s (surrounding) archaeology Moyano and Bustamante (2010) provides entrees to link cultural, geographical, climatic, biotical, astronomical, atmospheric and psychological information from ethno-archaeological data in small, medium and large scale. It strengthens the concepts of Landscape archaeology Bradley (2000) and the Xi'An Declaration. http://www.international.icomos.org/xian2005/xian-declaration.htm

3. Methodology

4.

Materials

5. Objectives

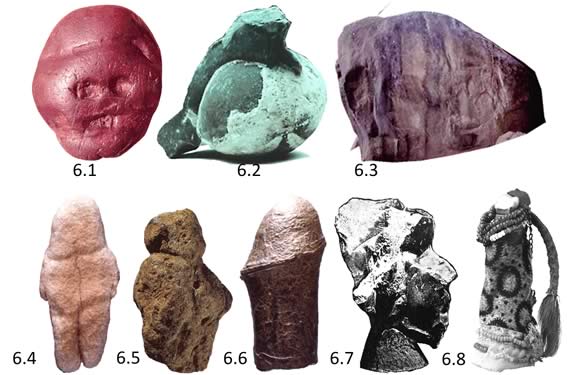

6. Examples sorted by date Following this, we present a small selection of Mimetoliths and Mimetomorphs from 3

million years BP to 2,000 years BP. Each object represents a period and not a

specific date. The available examples are numerous, and due to length

restrictions, it is not possible to present more.

6.1 Makapansgat, 3 millions of years BP

Makapansgat cobble, which are of such effective

iconic properties that they were noticed by hominids up to three million years

ago. (Bednarik 2008).

j) pampbird3, Identified as 'bird with fossil inclusion' by Ursel Benekendorff.

6.4 Tan-Tan Venus,

Morocco, 500,000 to 300,000 BP

6.5 Berekhat Ram, Female figurine, Israel. 470 000 to 230 000 BP Basaltic tuff pebble containing scoria clasts excavated in an Acheulian

occupation layer at Berekhat Ram, Golan Heights; (Bednarik (2006).

6.6 Erfoud, Morocco, Late

Acheulian, 200 000 to 300 000 BP

Fossilized fragment of a cuttlefish cast that

has the distinct shape and size of a human penis. Bednarik (2006).

Heads / h) hwhdwhat, "40.1.

Kopf mit Kappe von Wittenbergen. Nr. 3,1." http://www.originsnet.org/hambwitt2gallery/pages/h%29hwhdwhat.htm

6.8 Katonga River basin, Paleolithic

A phalangeal ‘doll’

from the, Yenisey Uezd District, Yenisey Governate/Province in central Siberia,

11 cm. Beads, cloth and a reindeer phalange. (Caldwell 2009).

Figure 1:

Mimetoliths and Mimetomorph.

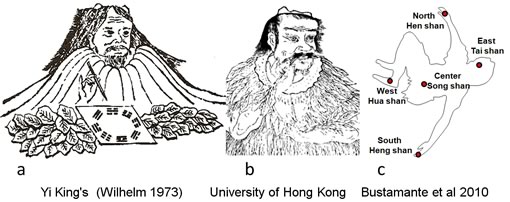

6.9 Three Chinese gods.

Three mythological characters described as possible sacralized elements of the natural landscape in the origin of all belonging to the formative period of the Chinese culture (Bustamante et al 2010): Fu

Hsi (伏羲): mythological emperor, a culture hero invented writing, fishing, and trapping. Possible in

their origin was a mountain. (figure 2 a).

Shen

Nong (神农): mythological emperor established

a stable agricultural society in China. Possible in their origin was a mountain. (figure 2 b).

Pan Gu (盘古): Central figure in Taoist legends of creation. After dead his body became in the five sacred mountains of China (figure 2 c).

Figure 2: Three Chinese Mimetoliths.

7.1 From the

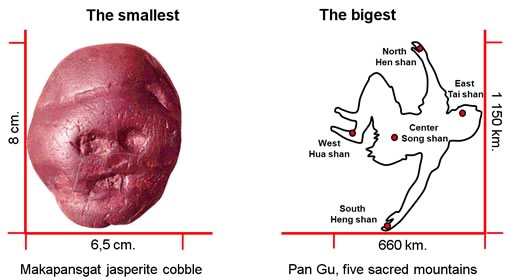

smallest and simple to the biggest and complex

Makapansgat: Mimetolith (M). The

earliest evidence of the phenomenon known as pareidolia. If pareidolia allows

to explain the origins of art, this mimetolith dates it in a range of 2.5 to 3

million years BP.

GROß PAMPAU: Mimetolith (M). Findings from this period (500,000 years BP) may be considered as early manifestations of the symbolic though. The first expressions of apophenia (to relate this rock with a bird and as a symbol of communication with heaven) and hierophany (perception of the phenomenon as numinous) are probably linked to this epoch. Guimaraes

say: “Selective activity precedes and prepares the

production of graphic marks, symbols and patterns. A process that, according to

Bednarik, will later result on to the invention of art. From

"reading" to "writing" perceptual-symbolic patterns in

reality”. (http://arthistorypart1.blogspot.com/2007/11/proto-art-and-paleo-art.html). Pareidolia can explain that process.

Berekhat Ram: example of Mimetolith modified

(M-m). Back in this period, our

ancestors had the capacity to recognize a human shape on mimetoliths, probably

relate it to a ‘superior’ being and alter it to enhance the resemblance. This

may be considered as a prehistoric referent of the psychological origins of

art.

Tan-Tan Venus: Mimetolith modified

(M-m). The figurine bears microscopic traces of a red pigment,

which is currently the earliest evidence of applied coloring material. This case is similar to the previous

one.

Katonga River basin: Mimetomorph modified

(Mm-m). According Caldwell (2009) “The use of phalangeal figurines from central Siberia

to Greenland also suggests that the practice spread around the Arctic from

ancient sources”. Mimetomorphs can be made

out of biodegradable materials (bone, Wood, textiles) therefore the number of

objects found may be considerably minor than the number that actually existed.

China. Fu Xi, Shen Nong, Pan Gu: Mimetoliths (M). Shows documented cases of

sacralized mountains. Big scale mimetoliths, show the up scaling complexity of

the phenomenon. Pan Gu is the greatest Mimetolith found at present, 1,150 km.

by 660 km.

Figure 3: Mimetolith A) Makapansgat, the smallest. B)

Pan Gu, the bigest.

How many mimetoliths

or mimetomorphs might have been discarded in diverse archaeological sites? Now

that we are able to identify them it is possible that in the future we will

find dated further back in time.

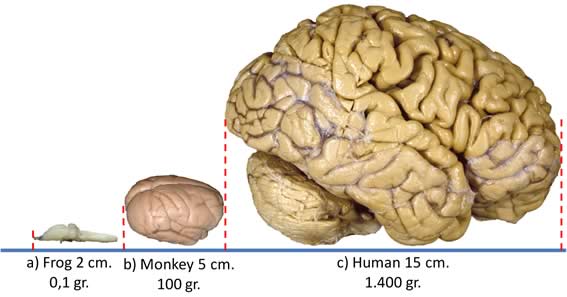

Figure 4. human brain

evolution Mimetoliths and Mimetomorphs.

The effects of

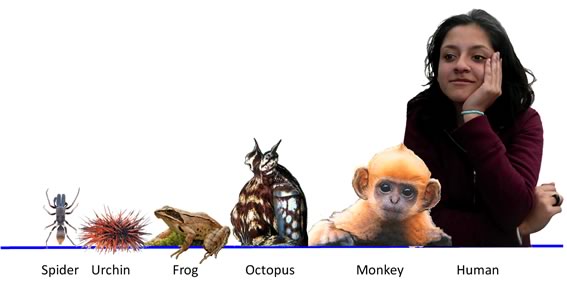

pareidolia appear to have influenced not only human beings, but also animals.

Here we present five examples of this: “We and other animals all are predisposed,

then, to see ambiguous phenomena as alive. In our case, we also are disposed to

see them as humanlike. Occasionally we are right, and these instances justify

the strategy. Often we are mistaken, and if we later see this, we call the

mistakes animism or anthropomorphism”. Guthrie. (2001).

Five

examples:

-ant-mimicking spider: Aphantochilus rogersi is an ant-mimicking spider that preys exclusively

on cephalotine ants. (Castanho y Oliveira, PS, 1997).

Frog and sea urchins “Just as frogs are prone to see moving dots

on a screen as flies, and sea urchins will avoid any dark shadow as if it were

an enemy fish, humans too tend to interpret their environment with the

"models generated by their most pressing interests" (Guthrie

1996: 418; 2002: 54, cited by Westh 2009)”.

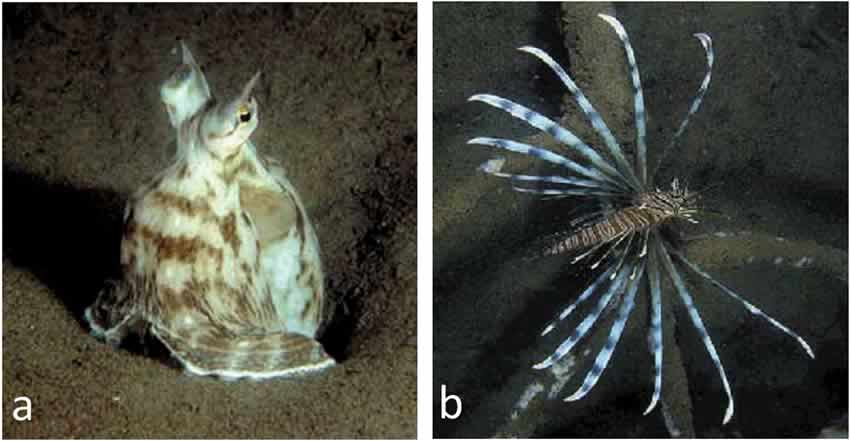

“We observed nine individuals of this species displaying a repertoire of postures and body patterns, several of which are clearly impersonations of venomous animals co-occurring in this habitat... …Additionally, our observations suggest that the octopus makes decisions about the most appropriate form of mimicry to use, allowing it to enhance further the benefits of mimicking toxic models by employing mimicry according to the nature of perceived threats”. Norman et al (2001). Figure 5 shows two

different shapes adopted by this octopus.

“Face perception is a skill crucial to primates…. …Almost all (97%) of

the visually responsive neurons in this region were strongly face selective,

indicating that a dedicated cortical area exists to support face processing in

the macaque.” Tsao et al (2006).

In their conclusions it can be read “Why is it important that the brain contains

an area consisting entirely of face-selective cells? First, this indicates that

the brain uses a specialized region to process faces”… This indicates that

our primate ancestors were in conditions of recognize mimetoliths.

Figure 6

Animals and Pareidolia.

7.4 Mimesis and Pareidolia

Pareidolia does not depend on the size of the brain. Hallow to explain a) perceptual errors (false recognition), b) the mimiking (To resemble closely; simulate:), c) The camouflage (concealment by some means that alters or obscures the appearance). Figure 7 compares the sizes of a human brain with the brains of a monkey and a frog.

There are no specific

studies about pareidolia on animals, but, it is possible to conclude based on

circumstantial evidences, that a high percentage of animals may use it to

recognize their predators, preys or others, as survival mechanism.

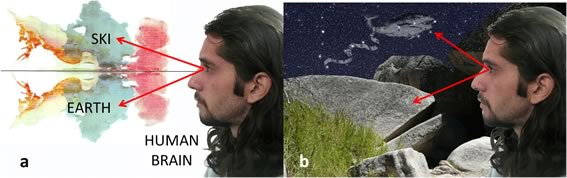

7.5 The

language of nature

Probably, human beings

tried to decipher the “language of nature” from the beginning. Thanks to Pareidolia,

it seems like they read the cosmos, the sky and the land as if they were a

gigantic Rorschach test that allowed them to see figures in the sky and the

land.

By means of apophenia and

hierophany, those figures were interpreted according to their context and to

what they seemed to suggest, always coming up with a coherent explanation in

relation to the happenings and observed events.

Figure 8 explains the

process: A) the observer explored the signs in the sky and the land as if they

were a Rorschach test. The human brain is the "most

existing complex computer B) when an apparent figure appeared on the

land a similar one did on the sky. It must have been a specialist task,

probably for chamans, to establish intricate relations and discover the

different cycles of nature (the 4 seasons, length of the year, and others).

Legends probably arose as a

record of the diverse phenomena observed and the relations linking them,

elaborating stories that contained the keys to recognize this phenomenon. The

key to understand these events and compose this tales was to identify common

components (constellations for example) connecting unknown occurrences with

well known objects and characters. By doing that, it was easier to individually

remember them, set up categories and connections and eventually recognize

changes in a certain period of time.

Possibly, whoever had this

special ability turned into the interpreters of the “God’s plans”, with a

special knowledge of the sacred and a particular power over the sky, the land

and the rest of men. This, eventually, may have led to the origin of structured

religions.

According to Rubia (2005) “the biological adaptation

has nothing to do with copying reality; to adapt means to find possibilities

and means to overcome resistances and obstacles in the experienced world”. The

PAH triad empirically explains the way this process took place.

7.6 Fertility cult., Apophenia and

Hierophanía

If there is a cult

devotes to a certain object associated to natural events, we are in position to

affirm that we are in presence of Apophenia and Hierophany. About the Palaeolithic figurative art of Eastern Europe and Siberia, Poikalainen (2001) in the conclusion says:

“The most evenly represented

motif in the area under discussion is female figurines or the sc. Palaeolithic

Venus figures. Their largest scale distribution and detailed elaboration

reflects how the worldview of a Pleistocene man was connected to the fertility

cult. Some paintings discovered in the Ignatievka cave also refer to the

fertility cult.”

J.D. Lewis-Williams and T.A. Dowson (1988) in their article 'The Signs of All Times' propose the Origin of Art in Entoptic Phenomena in time to the Upper Palaeolithic by which we can gain insight into the nature of the origins of art. Guthrie (1993) explain religion as systematic anthropomorphism. According to Clottes (2003) our Cro-Magnons ancestors were exactly like us: our direct lineage begins in Africa, at least 120,000 years ago; the alter states of consciousness are an intrinsic component of the human neuropsychological background. Vitalino (2007) associates myths and geographic formations (geomythology), describing myths and the relation with mythology, but fails to make a deeper study of the psychological phenomenon that justify it. Helvenston and Hodgson (2010) base their interpretation on neurophysiology. The

PAH triad offers an adequate theoretic model that allows to explain this

phenomenon. It clarifies the origin of paleo art, its relation to animism and

the possible origin of shamanism and religion, based on psychological

mechanisms inherent to human beings, making unnecessary an altered state of

consciousness, but may be favored by them. “Religious ecstasy is the extraordinary, not

tipical response” (whitley 2009, 195).

The PAH triad as a methodology

has multiple scopes, from the study of paleo-art to the development of methods

to study cultural astronomy.

7.10 The

origin of symbols.

The PAH triad may explain

the origins of sacred art. Acording Whitley

(2009, 178) “Borrowing again from native

America, despite the potential inferential hazards in doing so. I recognize

that in shamanistic cultures, painting and engravings are material objects

first and foremost, before they are signs or symbols. They exist because not

someone placed then there, but simply because they are there as physical

entities in their own right. In native american eyes, they have a life and

an agency of their own, with or without human involvement. Indeed in many

native American cultures human creation of the art is consistently denied”.

At

some point, natural shapes (mimetoliths-mimetomorphs) might have triggered the

shapes created by humans “transforming the given in to the created” (Whitley

2009, 48), but, the natural forms continued being valued through time, Most

likely as “divine creations” or with an intrinsic power.

Modern aniconic cultures (islamism, judaism…) still consider sacred certain symbolic figures, sites or rocks and others (Bustamante 2008 c). This indicates that natural tendencies are strong and with deep psychological roots. 7.11

What does it look like?

Archaeology

studies only show a drawing (petroglyph) but fail to assign any of value to

the mount or the surroundings. It is precisely in those where traces of the

PAH triad are found.

When we first learned to consider the appearance of the surroundings, meaning

massing, lights and shadows on rock formations and mountains, we found the

relations that led us to look for an explanation based on psychological

mechanisms and the rules of perception. (Bustamante 2004, 2005 a, 2005 b,

2005 d, 2006 a).

The question What does it look like? Is currently oriented towards the search

for mimetoliths and mimetomorphs when we observe an object or event in an

archaeological context (Bustamante 2008 a). This change in the question and

therefore in the validation criteria is coherent with what was indicated by

Maturana (2006).

7.12 Euhemerism the origin of the gods.

In occident, the search

for a rational explanation, based on actual facts, beings or objects for the

origin of the gods finds its source in Euhemerus a Sicilian

Philosopher about 300 - 260 B.C.. His method of rationalization is known as Euhemerism, cited by Diodorus (1970), that treats mythological accounts as a reflection

of actual historical events shaped by retelling and traditional mores.

PAH

shows the mechanisms that transformed into gods certain celestial elements,

natural event, features in the landscape and others. This explains what Hume

indicates “We find human faces in the

moon, armies in the clouds; and by a natural propensity … ascribe malice or

good-will to everything that hurts or pleases us. Hence… trees, mountains and

streams are personified, and the inanimate parts of nature acquire sentiment

and passion.(David Hume, Natural History of Religion, p. 29, cited by Gutrie 2001).

Acording the Legend, “Pyrene is the nymph of classical mythology who gave its name to the

Pyrenees. The legend attempts to explain how a mountain range that was

worshipped as a god by the early inhabitants came to be. Heracles,

(Hércules) deeply moved by Pyrene’s tragic ending burned by the fire of Gerion, erected a mausoleum

over her dead body, by piling up all the stones and rocks he could find, thus

creating a great mountain range that he called the Pyrenees in memory of

Pyrene” http://www.caiaragon.com/en/arbol/index.asp?idNodo=119&idNodoP=38

Figure 9: Pyrenees as the body of Pirene.

The Pyrenees provide an example of the PAH triad in the geographic

surrounding. The mimetolith of Pirene has a total length of

400 km. Gerión was the founder of Gerona and the surrounding area of

Garrocha, a volcanic region (Pallí and Pujadas, 1999). The last eruption

dates back around 9,500 BP. This may explain the fire in the legend.

7.14

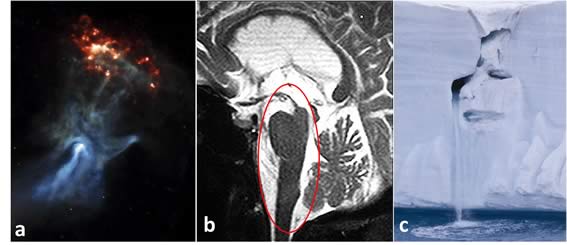

Modern PAH.

The

PAH triad still applies to modern discoveries, not only among common people,

but with world class scientists. It is a useful tool to explore the world,

but the religious and emotional connotations have changed. The following

examples show how this method is unconsciously applied in today´s science:

Astronomy, cosmic hand:

NASA inform in the article A Young Pulsar Shows Its Hand, (04.03.09) “At the center of this image made by NASA’s Chandra

X-ray Observatory is a very young and powerful pulsar, known as PSR B1509-58,

or B1509 for short. The pulsar is a rapidly spinning neutron star which is

spewing energy out into the space around it to create complex and intriguing

structures, including one that resembles a large cosmic hand”. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/chandra/multimedia/photo09-025.html,

(Moyano, Bustamante, 2010, figure 6).

Maranhão-Filho and Vincent (2009) says in the Conclusion “Various imaging techniques have developed

largely as useful diagnostic tools in modern medicine. Facing a multitude of

contrasts and forms, our brains naturally react trying to find familiar

patterns matching typical aspects of a certain disorder. This process is

similar to finding visual patterns in shadows and clouds, i.e. pareidolia. In

terms of neuroimaging, some disorders may present aspects that evoke animals

and suggest pareidolic denominations. Such visual illusions help memorization

and improve general diagnostic skills”.

Ecology, the face of mother

nature:

“Marine photographer and environmental lecturer

Michael Nolan captured the pictures while on an annual voyage to observe the

largest icecap in Norway Austfonna on July 16… describes it as …'Tears' in

the natural sculpture were created by a waterfall of glacial water falling

from one of the face's 'eyes'”.

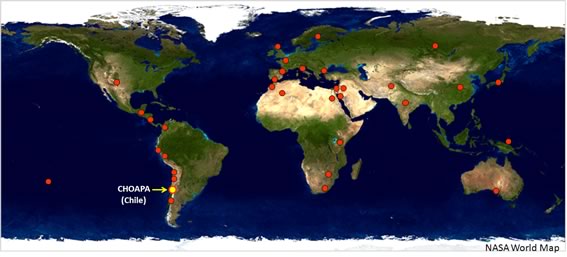

7.15 PAH as a

global phenomena

During field works, using methods that were non aggressive to the site (meaning without major interventions or disruptions such as digging) we found this phenomena in pre-columbian cultures first in Chile (Choapa region), Peru, Bolivia and Mexico. Later, we found in specialized literature traces of this coming from the 5 continents and from all periods of history. Then the PAH triads appears to be a ubiquitous phenomena (Bustamante 2008 c).

Figure 11: Probable

ubiquity of the phenomena. Each red dot represent a site where we found PAH.

8. Conclusions

Pareidolia: it provides a way to be related to

the world, to interpret cosmics signs visualizing the sky and the land as if

they were a gigantic Rorschach test, contributing to the origin of Paleoart,

being Makapansgat cobble

its earliest manifestation, and the Mimetolith of Pan Gu the latest and most

complex (in relation to the period studied in this article).

The implications of Pareidolia include all 5

senses in the formulation of images. This can be observed in both humans and

animals. As a result of this process in humans, we found gods that arose from

the combination of this images and human emotions.

The

examples of pareidolia in animals indicate that it might be phenomena inherent

to living creatures, independent of the cerebral development.

Apophenia: it allows establishing relations between different beings, things

uncertain events, phenomena and others not directly related. When the observer

finds significant matches a Hierophany is produced, meaning, a feeling that what was observed is linked to sacred

matters.

The PAH Triad: A) it

provides a theory-perceptual frame that does not depends on altered states of

consciousness. It allows explaining in part the emergence of animism, religion

and art, by means of psychological phenomena inherent to all human beings, from

any period of history. B) it appears to be an ubiquitous

phenomena. C) It might be a precedent of science.

What does it look like?: This question applied

to archaeological contexts, permits a change in the paradigm, work

methodologies and validation techniques.

Mimetoliths

and Mimetomorphs: Seem to detonate the work

of the PAH triad.

Archaeology of the Entorno (Surroundings): Supplies a method to relate data from diverse fields such as culture, geography, climatology, astronomy, psychology and biology among others.

—¿Preguntas, comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com— Cómo citar este artículo: Bustamante D., Patricio., Yao, W. Fay., Bustamante, Daniela. Search for meanings: 2011

BIBLIOGRAPHY Bednarik, Robert G., 2006, Lecture No. 3., The

evidence of paleoart, Semiotix Course Cognition and symbolism in human evolution. http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/epc/srb/cyber/rbednarik3.pdf

Bednarik, Robert G., 1994, A taphonomy of

palaeoart, Antiquity 68. 258, March, 1994: 68 (7 pages) http://cogweb.ucla.edu/ep/Art/Bednarik_94.html

Birrell Anne, 2000, Chinese Myths, University of Texas Press,

Biron David, Libros

Pazit, Sagi Dror, Mirelman David & Moses Elisha, 2001, Asexual reproduction: 'Midwives' assist dividing amoebae, Nature 410, 430 (22 March 2001). doi:10.1038/35068628

Bustamante

D. Patricio, 2005 a, Entorno: Obras Rupestres, Paisaje y

Astronomía en El Choapa, Chile. http://rupestreweb.info/elmauro.html

Bustamante Patricio, 2005 b, Relevamiento de Sitio

Arqueológico de Cuz Cuz, IV Región, Chile: Descripción de una experiencia.

Parte I. Relevamiento y rescate de los diseños. http://rupestreweb.info/bustamante.html

Bustamante D. Patricio, 2005 d, Relevamiento de Sitio Arqueológico

de Cuz Cuz, IV Región, Chile. Parte II. Aproximaciones a una Metodología para la Interpretación de las Obras

Rupestres en Relación con el Entorno. http://rupestreweb.info/busta2.html

Bustamante D. Patricio, 2006 a, Hierofanía y Pareidolia Como Propuestas de E xplicación Parcial, a la Sacralización de Ciertos Sitios, por Algunas Culturas Precolombinas de Chile. http://rupestreweb.info/hierofania.html Bustamante D. Patricio, 2008 a. ¿Qué Parece? Como Pregunta Orientadora en el Estudio de la Topografía

Sagrada en la cultura Azteca. http://www.rupestreweb.info/queparece.html

Bustamante D. Patricio, 2008 c, Posible Ubicuidad Espacio-temporal de la triada

Pareidolia-Apofenia- Hierofanía, como probable origen de la

sacralización de algunos elementos del paisaje. http://www.rupestreweb.info/triada.html

Bustamante D. Patricio, Yao

Fay, Bustamante Daniela, 2010, The worship to the mountains: a study of the creation myths of the

chinese culture, http://www.rupestreweb.info/china.html

Caldwell Duncan, 2009, Palaeolithic whistles or a

preliminary survey of pre-historic phalangeal figurines. Rock Art Research - Volume 26,

Number 1, pp. 65-82.

Castanho, LM | Oliveira,

PS, 1997,

Biology and behaviour of the neotropical ant-mimicking spider Aphantochilus

rogersi (Araneae: Aphantochilidae): nesting, maternal care and ontogeny of

ant-hunting techniques Journal of Zoology [J. Zool.]. Vol.

242, no. 4, pp. 643-650. Aug 1997.

Clottes Jean, 2003, Chamanismo en las cuevas paleolíticas, Ponencia defendida ante el 40

Congreso de Filósofos Jóvenes (Sevilla 2003) http://www.nodulo.org/ec/2003/n021p01.htm

Dietrich

R. V, 1989, Image: Another Mimetolith, Rocks & Minerals.

Diodorus of Sicily, 1970, The

Library of History, book VI, Cambridge, translated by C. H. Oldfather,

volume 3.

Guimaraes

Lima Marcelo, 2007, Introduction to the

History of Art, Part 1: From Prehistoric Art to Early Renaissance copyright (C)

Paleoart - The Oldest "Work" of Art?, http://arthistorypart1.blogspot.com/2007/11/proto-art-and-paleo-art.html

Gray

Louise, 2009, Icecap photo shows 'mother nature in tears', Telegraph.co.uk, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/earthnews/6127552/Icecap-photo-shows-mother-nature-in-tears.html

Gombrich Ernst, 1959, The Story of Art. London: Phaidon. Guthrie Stewart, 2001, Why

Gods? A cognitive Theory,. Religion in mind: cognitive perspectives on religious belief, ritual, and

experience, Chapter 4, Edited by Jensine Andresen, Cambridge University Press.

Harrod

James, 2006, INDIA

Bhimbetka , Auditorium Cave, Madhya Pradesh: Acheulian Petroglyph Site, http://www.originsnet.org/bimb1gallery/pages/i%29%20bmbcr1.htm

Helvenston and D. Hodgson N.,2010, The Neurophisiology of Animism: Implicatios for

Understanding Rock Art.Rock Art

Research 2010 - Volume 27, Number 1, pp. 61-94. P. A.

Lewis-Williamsand

J. D., Dowson T. A., 1988, Current

Anthropology Volume 29, Number 2, April, DOI: 10.1086/203629

Maturana Romesín Humberto, 2006, ¿Qué es la ciencia? Entrevista, http://elproceso.blogspirit.com/archive/2006/09/10/humberto-maturana-premio-nacional-de-ciencias-de-1995.html

Moyano

V. Ricardo, Bustamante Díaz Patricio, 2010,

Socaire’S Entorno (Surrounding), Northern Chile: A Four-Dimensional Interpretation of Andean World View,. The

38th Annual Midwest conference. http://www.ipfw.edu/anthropology/MWCAAAE/Program.html

Norman Mark D., Finn Julian and Tregenza Tom, 2001, Dynamic

mimicry in an Indo- Malayan octopus, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B , 2001,1755-1758 268

Pallí Lluís y Pujadas Albert, 1999, El campo volcánico Catalán, Enseñanza de las Ciencias de la

Tierra, 1999. (7.3), 229-236

Tilley Christopher, 1994, A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

Väino Poikalainen, 2001, Paleolithic art from Danube to Lake Baikal. Folklore Vol. 18&19, Folk Belief and Media Group of ELM, http://www.folklore.ee/Folklore/vol18/paleoart.pdf Vitaliano Dorothy B., 2007, Geomythology: geological origins of myths and legends, Geological Society of London. http://sp.lyellcollection.org/cgi/reprint/273/1/1.pdf

Whitley David, 2009, Cave Paintings and the human

spirit., Prometheus Books, page. 178.

Wilhelm Richard, 1973 Livre des transformations allemande Version of, Librairie de Médicis,

3, rue of Médicis, Paris.

Yang Lihui, An Deming, Anderson Jessica, 2005, Handbook of Chinese Mythology, ABC-CLIO. [Rupestreweb Inicio] [Introducción] [Artículos] [Noticias] [Mapa] [Investigadores] [Publique] |

Search for meanings: from pleistocene art to the worship of the mountains in early China. Methodological

tools for Mimesis.

Search for meanings: from pleistocene art to the worship of the mountains in early China. Methodological

tools for Mimesis.