|

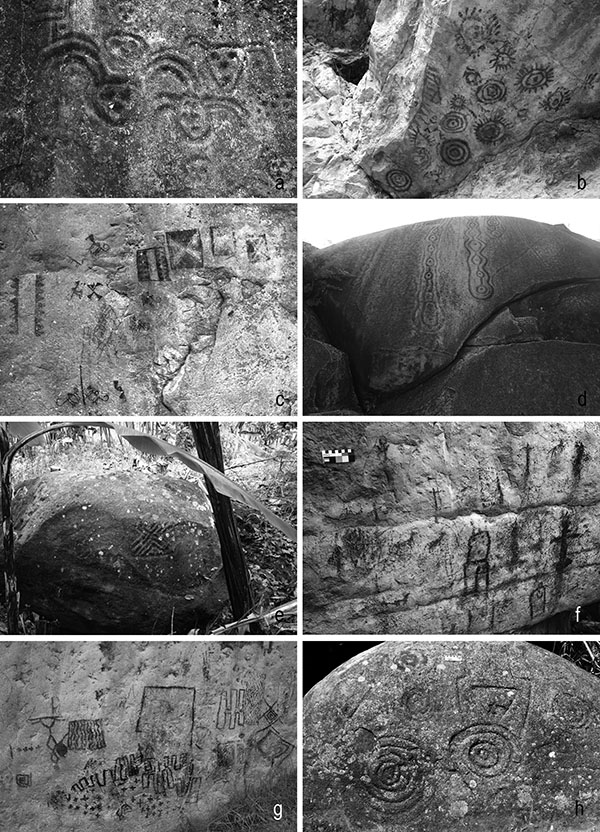

| Fig. 1. Some of the Colombian rock art sites documented in the last few years. a. San Jacinto, (Bolívar), b. Sáchica (Boyacá), c. Sutatausa (Cundinamarca), d. Floridablanca (Santander), 4. e. Zipacón (Cundinamarca), f. Cucunubá (Cundinamarca), g) Sutatausa (Cundinamarca), h. Chinchina (Caldas). Diego Martínez C., 2006-2010, Pedro Argüello, 2009. |

|

Chronology is one of the

most challenging topics in rock art research around the world (Whitley 2005).

Although the dating of rock art is not a goal in itself, it is a fact that

chronological accuracy is pivotal in order to understand the social context in

which rock art was produced and used (Argüello 2008, 2009). In Colombia, almost

all attempts to explain rock art have been made without a solid chronological

basis. This lack of dating has not allowed the building of a credible explanation

of rock art’s context. There is a general tendency to assign rock art to the

Indian groups described by Spanish chronicles during the 16th century, without

taking into consideration the fact that the places in which rock art exists

were populated for at least 10,000 years (Correal & Van der Hammen 1977).

Over such a long period of time diverse groups with political, economic and

cultural differences settled here in succession.

Contrary to the worldwide

tendency for a growing number of archaeologists to be interested in the study

of rock art, in Colombia the increasing number of archaeologists is inversely

proportional to the number of them studying rock art (Jaramillo & Oyuela-Caycedo 1995). Although several archaeological

publications contain information about this subject, in most cases rock art is

not integrated with the problems treated by archaeologists in their analyses

and just constitutes an addendum to the archaeological reports (i.e. Langebaek & Piazzini 2003:

70; Mora 2003: 85). Part of this situation has its origins in the incapacity of

archaeologists to assign chronology to rock art, which prevents them linking it

to other archaeological material. And to some extent it is the result of the

Colombian academic tradition that has assigned a privileged role to other kinds

of archaeological evidence (i.e. ceramics, lithics)

as a source of information about the past.

In recent years, two

research projects have been carried out with the explicit aim of understanding

rock art in an archaeological context (Castaño &

Van der Hammen 2006; Argüello 2009). To determine what an archaeological perspective in rock art research

implies is a difficult task because of the plurality and diversity of

archaeological approaches (e.g. Chippindale & Taçon 1998). However, these two projects appeal to a traditional archaeological

approach consisting of the recovery of archaeological material near rock art

sites as a way to contextualise and date related

activities. Although their results are preliminary and not necessarily

conclusive, these projects have shown that, in fact, it is possible to recover

the remains of activities that were possibly linked to the production and use

of rock art, and they have opened the door to a promising perspective for an

archaeological association of rock art.

Although archaeological

excavations close to rocks with paintings and petroglyphs are at present

limited in number, they have demonstrated the diversity of contexts in which

rock art was involved. Excavations by Castaño &

Van der Hammen (2006) of rock-shelters in Chiribiquete (southeastern rainforest region) suggest that

such sites were constantly visited –but were not habitation sites–

and ritual and ceremonial activities were probably carried out in immediate

vicinity of panels with rock paintings. Such activities, according to the

authors, would be related to “shamanic” activities. The “shaman”’s presence would be corroborated by the formal characteristics of the paintings

– representation of phosphenes, “shamanic”

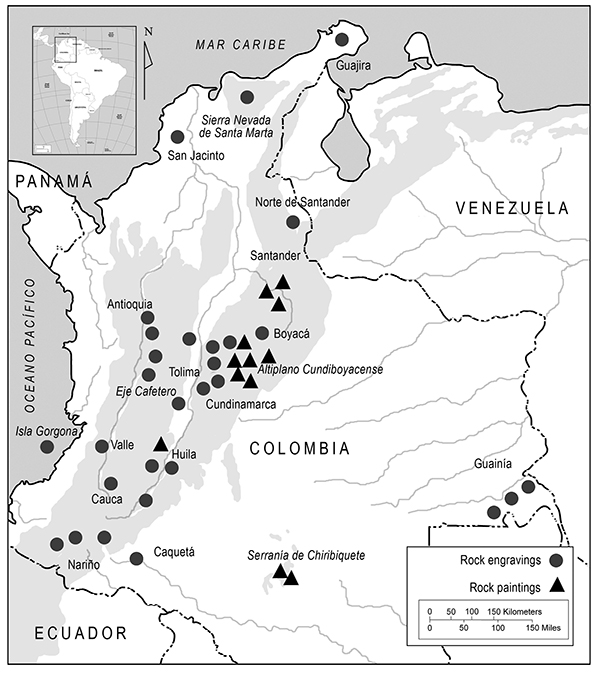

animals, and ritual scenes (Fig. 3). On the other hand archaeological

excavations in El Colegio (Cundinamarca) (Argüello 2009) seem to have found a different context in

which rituals would be associated with domestic activities.

|

| Fig. 3. Transcription of a portion of rock paintings from the Abrigo de Los Jaguares (Chiribiquete). Drawing by Diego Martinez based on a photo by Carlos Castaño Uribe, 2005. |

Regarding the dating of rock

art, Castaño & Van der Hammen (2006: 41) assert that the rock paintings of Chiribiquete were made between 450 and 1450 AD although some findings apparently suggest the

existence of older rock paintings. This date is based on the presence of remains of pigments and fragments

of rocks with paintings detached from rock-shelters and stratigraphically associated with charcoal and other archaeological artifacts. Unfortunately, no

analysis of pigments from archaeological deposits and murals has been carried

out in order to confirm that the pigments are in fact the remains of paintings.

This means that definite confirmation of the age of the Chiribiquete rock paintings has to wait until a specialised pigment analysis has been done.

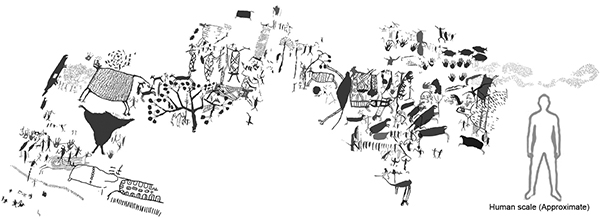

Archaeological excavations

at El Colegio (Fig. 4) have made possible the dating

of activities associated with rock art use. Two kinds of activities seem to be

related to the placing of offerings at the edges of rocks with petroglyphs. In

fact, fragments of rocks with petroglyphs and cupules as well as cobbles have

been excavated close to the main rocks (Argüello 2009). Other activities such as hearths have

also been identified in the immediate vicinity of petroglyphs. Pottery sherds associated with these activities have been dated to

between 2100 and 1100 BP, suggesting the period during which petroglyphs were

probably used.

|

| Fig. 4. Cavity in a rock with petroglyphs in which some “offerings” were found. El Colegio (Cundinamarca). Pedro Argüello. |

In short, contrary to the

belief that a traditional archaeological approach to rock art is futile, both

the Chiribiquete and El Colegio cases have demonstrated how the responsible application of archaeological

methods is a powerful tool for answering basic questions about the more complex

problems that remain. Unless we decide to opt for the uncritical application of

universal theories, we have to accept the necessity of building a solid basis

for the comprehension of rock art, part of which is the uncertain chronology.

Beyond academic concerns,

perhaps one of the most important results of the above-mentioned archaeological

projects is the re-evaluation of the definition of rock art site (Martínez, 2005b). It has

been traditionally considered that the site is just the rock with paintings or

petroglyphs; but now it is necessary to accept that the archaeological deposits

around these rocks are part of it as well. Such a statement implies new

considerations regarding the protection of rock art sites because it is a

common practice to loot these sites in search of Indian treasures. Therefore, documentation projects should be accompanied by

an educational campaign in order to avoid that new sites could be vandalized.

Rock Art as Cultural Heritage. Conservation, education and presentation

According to the Colombian

Political Constitution (1991), every archaeological object belongs to the State.

Rock art is considered a constituent part of the National Archaeological Heritage

and is dealt with by the Special Regime of Archaeological Heritage (art. 54 t.IV, Dec.763-2009) whose

principal objectives are protection, recovery, conservation and presentation.

This legal framework, developed during the last decade, has made possible some

progress in the conservation of archaeological material, although a convincing

State policy is still necessary. Although the law is mandatory about the obligation

to carry out CRM archaeology in almost every civil project involving soil

removal, the expansion of the urban frontier is still perilous for both rock

art and its surrounding context, mainly because companies working in civil

projects do not know the law or arbitrarily violate it. But even worse, many

rock art sites are destroyed through lack of knowledge about the correct

management of this cultural resource by archaeologists practising CRM.

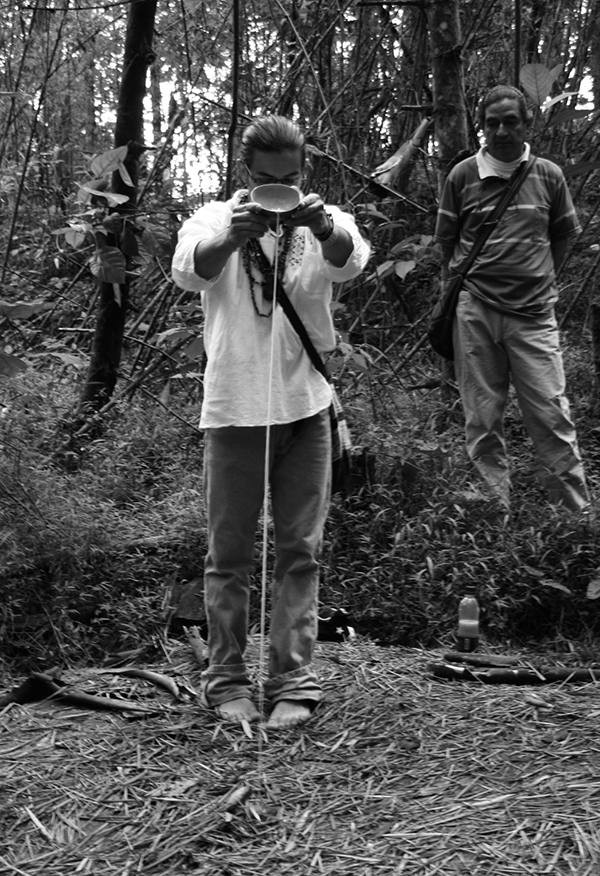

Concerns about the

preservation of rock art have been a growing field of interest in recent years.

The broad variety of issues that have been taken into account could be grouped

into a number of different topics. The most consistent effort has been focused

on the presentation of rock art. Target groups have been diverse, although

systematic processes have put an emphasis on local administrative authorities

(Botiva 2000), schoolteachers and students (Martínez &

Botiva 2004) as well as organised community groups

(Fig. 5). The scope of these educational projects was initially limited to the

centre of the country, and they were directed by the State agency responsible

for protecting archaeological heritage (Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia – ICANH) as part of an educational project

directed by archaeologist Alvaro Botiva. Since then, some similar attempts have

slowly been adopted in other regions (Gómez & Barona 2007). Although it is

difficult to evaluate the real effect of such educational programmes,

it is hopeful that some of the groups involved are using these materials as a

“point of departure” for demanding that administrative authorities pay attention

to rock art conservation, and as a source of knowledge about the topic. On the

other hand, the growing visibility of rock art has led some of these embryonic

groups to include it in projects of cultural and ecological tourism. However,

this might turn into a double-edged weapon, because it could allow rock art to

be protected by an informed community while exposing it to perils related to

poorly informed tourists.

|

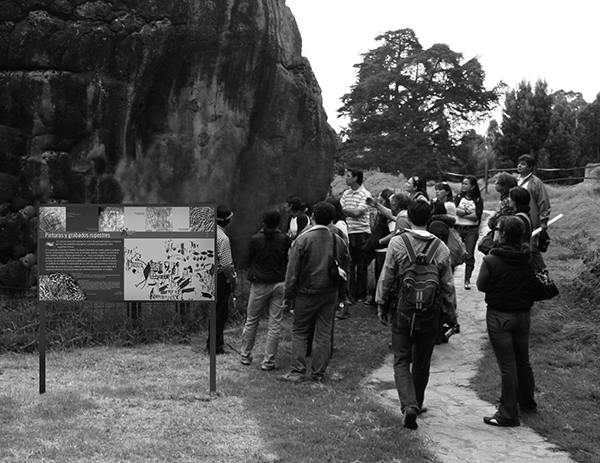

| Fig. 5. Schoolchildren participating in a rock art workshop. Zipacón (Cundinamarca). Diego Martínez C., 2009. |

|

| Fig. 6. Conservation work (graffiti removal) in Parque Arqueológico de Facatativa (Cundinamarca). María Paula Álvarez, 2005. |

We also have to consider the

way people think about and relate themselves to material from prehispanic communities. Colombia is a country of diverse

“ethnic” groups that have been differentially integrated (and sometimes just

excluded) in a failed attempt at national construction. Some of these groups,

frequently dubbed “ethnic minorities”, have a long history of struggle against

central State administration in an effort to maintain their lands, autonomy and

identity. An important component of these struggles consists of memory recovery

and the construction of historical narratives, most of them strongly related to prehispanic material such as rock art (e.g. Dagua et al. 1998: 65-66). In consequence, different and sometimes conflicting “versions”

about heritage ownership and management have emerged (Londoño 2003).

|

| Fig. 7. A “neo-Muisca” performing an offering with fermented maize beer –chicha– on a rock with petroglyphs in Sasaima (Cundinamarca). Diego Martínez C., 2009 |

With respect to the way in

which rock art is involved in claims by new social movements, there are three

topics that seem to be pre-eminent: concerns about the necessity of protecting

rock art sites, new attempts to explain rock art meanings, and the use of rock

art sites to perform different sorts of activities. The first two topics are

very welcome in rock art research, but the third brings a series of necessary

reflections. For example, Gómez (2009) relates the use of the rock paintings in

the Archaeological Park of Facatativá by a “neo-Muisca” priest in order to communicate with Muisca deities and to be instructed by them. As a

consequence, an increasing number of activities are taking place around rock

art murals. Some of them, like offerings and pledges, as far as we know, pose

no threat to rock art, but others like incense burning may cause damage to rock

paintings. In fact, recent inspections in the Archaeological Park of Facatativa have verified the existence of debris from

ceremonial activities performed by different groups (Fig. 8) (Martínez 2010).

|

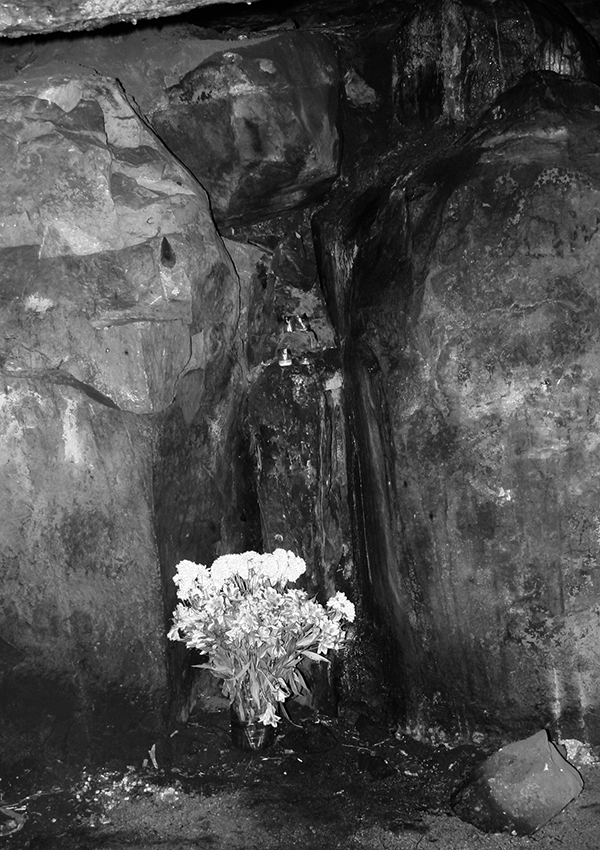

| Fig. 8. Offerings (flowers, candles, tobacco, contemporary pottery sherds) in a rock-shelter in the Parque Arqueológico de Facatativa (Cundinamarca). Diego Martínez C. 2009. |

Conclusion

Until recent years it was assumed

that Colombian rock art deserved only a marginal place in scholarly works which summarised knowledge

about this topic in South America (Dubelaar 1984; Schobinger 1997). This situation was due to several factors

such as the low flow of academic information between South American countries,

but more especially to the lack of comprehensive studies about Colombian rock

art that was almost limited to a few site descriptions. Luckily, this situation

has changed considerably as a result of considerable efforts by a growing group

of researchers interested in rock art studies. The use of new information

technology has made the diffusion and circulation of information about rock art

easier and cheaper. For instance, internet sites like

Rupestreweb (www.rupestreweb.info) have effectively integrated scholars in

Latin America and have become a tool for a very diverse audience. In addition, this tool allows some

researchers to make their studies known to a wider audience (Fig. 9).

|

| Fig. 9. Interpretative pathway in the Parque Arqueológico de Facatativa (Cundinamarca). Script and design Martinez & Botiva, 2008. |

The increasing volume of

available information about Colombian rock art has raised awareness of its

diversity and complexity. More than just “discoveries”, each new site, or group

of them, presents researchers with a new set of problems, and makes rock art

explanation ever more challenging. Two examples illustrate this point. Recent

discoveries of rock paintings in white and black in protected zones of

rock-shelters have permitted researchers to postulate that the pre-eminent

occurrence of red paintings in the centre of Colombia is a consequence of a taphonomic process (Argüello & Martínez 2004: Fig. 10) instead of a prehispanic cultural choice as was previously assumed

(Cabrera 1969). The finding of rock paintings inside some caverns in western

Colombia (Pino & Forero 2008), a region in which only petroglyphs in open-air sites had previously been

found, demonstrates that the view of the preferential spatial distribution of

different kinds of art is mostly related to the effect of the biased way in

which rock art is sought.

|

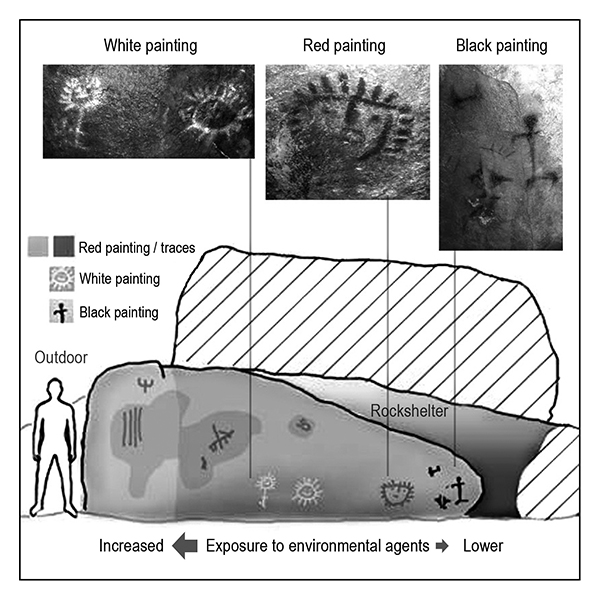

| Fig. 10. Differential distribution of rock paintings produced by taphonomic processes, Sutatausa (Cundinamarca). After Argüello & Martínez 2004. |

While researchers are

occupied by their goal of explaining rock art, they are also increasingly

concerned with issues related to rock art conservation. Nowadays it is not

possible to be involved in rock art research without facing problems associated

with the survival of the object of study. But it is not only a question of the

survival of the object itself; there are also the complex considerations such

as nationalism, heritage, and the economic use of prehispanic material. In short, Colombian rock art research is both a challenging endeavour and a productive field for exploring and

confronting current debates about this topic.

We are grateful with Carlos Castaño Uribe and María Paula Álvarez for provide photos for Figures 4 and 6 respectively

and James Williams for helping with English language in an early version of

this text.

![]()

—¿Preguntas, comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

Cómo citar este artículo:

Arguello García, Pedro; Martínez Celis, Diego Rock Art research in Colombia

En Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/rockartincolombia.html

REFERENCIAS

Álvarez, M.

& Martínez, D. 2004. Procesos de documentación y conservación en los conjuntos pictográficos

19 y 20, Parque arqueológico de Facatativá. Informe de investigación. ICANH: Bogotá.

Alzate, N. &

Osorio, C. 2009. Aproximación a una

contextualización histórica y cultural de los petroglifos del Valle de Aburra.

Tesis/Informe de práctica. Tesis (Antropologo). Universidad de Antioquia.

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas. Departamento de Antropologia: Medellín.

Andrade, J., León,

V. & Gonzalez, E. 2006. Pinturas

rupestres en palermo, huila. Testigos silenciosos en los santuarios católicos. Rupestreweb. Available at: http://www.rupestreweb.info/palermo.html

Argüello, P. 2006. Restauración y educación en

el arte rupestre. Notas sobre un caso colombiano (Parque Arqueológico de

Facatativá). Rupestreweb. Available at: http://rupestreweb.info/facaresta.html

Argüello, P. 2008. Tendencias recientes en la investigación del arte

rupestre en Suramérica. Una síntesis crítica. Arqueología Suramericana 4

(1): 53-75.

Argüello, P. 2009. Archaeology of rock art: a

preliminary report of archaeological excavations at rock art sites in Colombia. Rock Art Research 26

(2): 139-64.

Argüello, P. &

Martínez, D. 2004. Procesos tafonómicos

en el arte rupestre: un caso de conservación diferencial de pinturas en el

altiplano cundiboyacense, Sutatausa, Colombia. Rupestreweb. Available at: http://rupestreweb.info/sutatausa.html

Baena, J.,

Carrión, E. & Blasco, C. 2006.

Hallazgos de arte rupestre en la Serranía de Chiribiquete, Colombia. Misión

arqueológica 1992. Rupestreweb. Available at:

http://rupestreweb.info/chiribiquete.html

Bonilla, M. 2003. Programa de reconocimiento y prospección

arqueológica para el E.I.A y P.M.A. del área de influencia del proyecto

construcción y operación del propanoducto y planta almacenadora de gas licuado

GLP Mondoñedo. (m.s). Velogas: Bogotá.

Botiva, A. 2000. Arte rupestre en

Cundinamarca, patrimonio cultural de la nación. Gobernación de

Cundinamarca, ICANH: Bogotá

Cabrera,

W. 1969. Monumentos rupestres de Colombia (Cuaderno primero: Generalidades, algunos conjuntos pictóricos de

Cundinamarca). Revista Colombiana de Antropología. 14: 81-167. Bogotá.

Castaño-Uribe, C. & Van der

Hammen, T. 2006. Arqueología de visiones y

alucinaciones del Cosmos felino y chamanistico de Chiribiquete. Parques

Nacionales Naturales de Colombia, Corpacor, Fundación Tropenbos: Bogotá.

Chippindale, C. & Taçon, P. (eds) 1998. The Archaeology of Rock-Art.Cambridge

University Press: Cambridge.

Correa, J. 2002. Los

muiscas del siglo XXI en Chía: el Resguardo Indígena de Fonquetá y Cerca de

Piedra. Departamento de Cundimarca, Secretaría de Cultura: Alcaldía Popular de

Chía.

Correal,

G. &

Van der Hammen, T. 1977. Investigaciones arqueológicas en los

abrigos rocosos del Tequendama (Vol. 1). Fondo de Promoción de la Cultura

del Banco Popular: Bogotá.

Dagua, A., Aranda, M. &

Vasco, L. 1998. Guambianos: hijos

del arcoiris y del agua. Fondo Promoción de la Cultura, Fundación

Alejandro Angel Escobar, CEREC:

Bogotá.

Delgado, C. &

Mercado, R. 2010. La blasonería y el arte

rupestre Wayuu.Rupestreweb. Available at: http://www.rupestreweb.info/wayuu.html

Dubelaar,

C. 1984. A study on South American and

Antillean petroglyps.Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology: New Jersey.

Flórez, A. 2009. Piedras vivas: manifestaciones rupestres y memoria

oral en el

valle de Sibundoy, corredor milenario entre andes y selva. Rupestreweb. Available at:

http://www.rupestreweb.info/piedrasvivas.html 2009

Gómez, F. 2009. Los chyquys de la nación muisca chibcha: ritualidad, re-significación y memoria.

Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales-CESO, Departamento de

Antropología: Bogotá.

Gómez, T. &

Barona, A. 2007. Cartilla Pedagógica de arte

rupestre. Fundación Wayta Pachamama – Gobernación del Valle del

Cauca: Cali.

Gutiérrez, O. (ed.) 1999. Los muisca: un pueblo en reconstrucción. Cabildo

Indígena Musica de Suba. Foro Memoria e Identidad de los Indígenas Muisca de la

Sabana de Bacatá: Pueblo en Reconstrucción. Secretaría de Gobierno, Subachoque; Cabildo Indígena de Suba Resguardo

Muisca. Imprenta distrital: Bogotá

Hernández, D. 1998. Prospección Arqueológica y levantamiento de petroglifos en el

Municipio de Itaguí. Tesis/Informe de Tesis (Antropólogo). Universidad de

Antioquia. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas. Departamento de

Antropología: Medellín.

Jaramillo, L. & Oyuela-Caycedo, A. 1995. Colombia:

a quantitative analysis, pp. 49-68 in (A. Oyuela-Caycedo, ed.) History of Latin

American archaeology. Worldwide Archaeology Series 14, Avebury: Aldershot.

Langebaek, C. & Piazzini, C. 2003. Procesos de poblamiento en

Yacuanquer-Nariño: una investigación arqueológica sobre la microverticalidad en

los andes colombianos (siglos X a XVIII d.C.). Interconexión Eléctrica

S.A.: Bogotá.

Londoño, W. 2003. Discurso jurídico versus discurso cultural: el

conflicto social sobre los significados de la cultura material prehispánica. Boletín Museo del Oro 51. Available at:

http:/www.banrep.gov.co/museo/esp/boletin

López, E. & Velázquez, A. 2009. Aproximación al estudio iconográfico de las manifestaciones rupestres

en el municipio de Tamesis, Antioquia. Tesis/Informe de práctica. Tesis

(Antropólogo). Universidad de Antioquia. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y

Humanas. Departamento de Antropologia: Medellín.

Martínez, D.

2005a. Propuesta para la documentación

general de yacimientos rupestres: el petroglifo de la piedra de Sasaima,

Cundinamarca (Colombia).Rupestreweb. Available at:

http://rupestreweb.info/sasaima.html

Martínez, D. 2005b. Response to Munoz. The debate between GIPRI and ICANH-Double ethics in rock art research. Rock Art Research 22 (2): 202-03.

Martínez, D. 2006. Propuesta para un análisis iconográfico

de petroglifos: la piedra de Sasaima, Cundinamarca (Colombia). Rupestreweb. Available at: http://rupestreweb.info/sasaima2.html

Martínez, D. 2008a. Vallas

informativas y arte rupestre. ¿Visibilización de lo público o exposición de lo

frágil? Rupestreweb. Available at: http://www.rupestreweb.info/vallas.html

Martínez, D. 2008b. Arte rupestre, tradición textil y

sincretismo en Sutatausa (Cundinamarca). Rupestreweb Available at: http://www.rupestreweb.info/sutatextil.html

Martínez, D. 2010a. “Patrimonio cultural: no dañar” Dinámicas

y agentes en la relación patrimonio, cultura y sociedad. A propósito del arte

rupestre de la Sabana de Bogotá. Rupestreweb. Available

at: http://www.rupestreweb.info/pcys.html

Martínez, D. 2010b. Territorio, memoria y comunidad.

Aproximación al reconocimiento patrimonial del arte rupestre precolombino de la

sabana de Bogotá

. Rupestreweb. Available at:

http://www.rupestreweb.info/tmyc.html

Martínez, D. &

Argüello, P. 2003. Documentación del

yacimiento rupestre de Sáchica, Boyacá: informe final (m.s.) Calizas

y Agregados Boyaca S.A.: Bogotá.

Martínez, D. &

Botiva, A. 2004. Manual de arte rupestre

de Cundinamarca. ICANH – Gobernación de Cundinamarca, Segunda

Edición. Bogotá.

Martínez, D. &

Botiva, A. 2008. Exposición. Arte

rupestre Parque arqueológico de Facatativá. Patrimonio cultural, memoria e

identidad. Rupestreweb. Available at:

http://www.rupestreweb.info/expofaca.html

Martínez, L. &

Hernández, H. 2006. Identificación y

Caracterización del patrimonio Rupestre asociado a las áreas naturales de la

jurisdicción de Corantioquia. (m.s.), Corantioquia: Medellín.

Mora, S. 2003. Early

inhabitants of the Amazonian tropical rain forest: a study of humans and

environmental dynamics. Department of Anthropology, University of

Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh.

Moreño, A. 2009. Pensamiento ancestral y petroglifos. Una aproximación semiótica al

arte rupestre de Piragua –Cascajal en Timaná, Huila. Gobernación del

Huila. Secretaría de Cultura y Turismo. Fondo de Autores Huilenses: Neiva.

Muñoz, G. 2006. Patrimonio

rupestre. Historia y hallazgos. Gobernación de Cundinamarca, Alcaldía

Cívica de El Colegio: El Colegio.

Navas, A. &

Angulo, E. 2010. Los guanes y el arte

rupestre xerirense: la revelación de lo desconocido y el redimensionamiento de

lo antes firmado. Con la más completa muestra y análisis del Arte Rupestre

Mesetario realizado hasta el momento. Fundación El Libro Total: Bucaramanga.

Piazzini, C.,

Lozano, G. & López, L. 2002. Proyecto

hidroeléctrico Miel I: programa de rescate arqueológico. Informe final (m.s.) Informe presentado al Instituto Colombiano de Antropología / Ejemplar 2

en Cd-Rom bajo CD-ARQ-1163. Isagen, Strata: Medellín.

Pino, J. &

Forero, J. 2008. Acercamiento arqueológico al estudio de las expresiones

rupestres en un contexto de cavernas en el departamiento de Antioquia,

Colombia. International Journal of South American

Archaeology 2, February.

Pradilla, H. & Ortiz, F. 2002. Rocas

y petroglifos del Guainía. Escritura de los grupos arawak-maipure.

Fundación Etnollano, Museo Arqueológico de Tunja, Universidad Pedagógica y

Tecnológica de Colombia.

Pradilla, H. &

Villate, G. 2010. Pictografías,

moyas y rocas del Farfacá. Museo Arqueológico de Tunja, Universidad

Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Gobernación de Boyacá.

Quijano, A. 2007. El

pictógrafo quillacinga de “El higuerón” como marcador del solsticio de verano.

Empresa Editora de Nariño – EDINAR: San Juan de Pasto.

Quijano, A. 2010. Estudio matemático del diseño Precolombino de la

espiral en el arte rupestre des noroccidente del municipio de Pasto (Colombia). Rev.

Acad. Colomb. Cienc.

Xxxiv (no. 130): 53-70.

Ramírez, G. 2009. Petroglifos en el paisaje o paisaje en los

petroglifos.

Propuesta para analizar la apropiación cultural del paisaje

desde el

arte rupestre en la vertiente occidental de

Cundinamarca.

Rupestreweb. Available at: http://www.rupestreweb.info/anolaima.html

Restrepo, C. 2003. Proyecto de desarrollo vial doble calzada

Armenia-Pereira-Manizales, - Autopista del Café. (m.s.) Autopista del

Café, Instituto Nacional de Vías: Pereira.

Romero, M. 2003. Malikai, el canto del malirri. Formas

narrativas de un mito amazónico. Fundación Parature: Cerec.

Rodríguez, E. &

Pescador, L. 2004. Manifestaciones de

arte rupestre en la vereda El Fute, municipio de Bojacá: reconocimiento y

prospección arqueológica en el relleno Sanitario nuevo Mondoñedo. (m.s)

CISAN: Bogotá.

Secretaria de

Cultura de Norte de Santander 2007. Inventario

arqueológico, paleontológico y de arte rupestre de Norte de Santander, Colombia.

Informe presentado al Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, ICANH.

Instituto de Cultura y Turismo: Pamplona.

Schobinger, J. 1997. Arte

prehistórico de América. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes-Jaca

Books: México.

Whitley, D. 2005. Introduction to Rock Art Research. Left Coast Press:

Walnut Creek.