Aldea de Ramaditas, Chile: Architectural Art or Rock Art? Aldea de Ramaditas, Chile: Architectural Art or Rock Art?

Maarten van Hoek rockart@home.nl

INTRODUCTION

First it will be necessary to define

architectural art and rock art. Architectural art comprises all art forms

(engravings, sculptures, paintings etc.) that have intentionally been made to exclusively

adorn surfaces of anthropic (humanly made) constructions.

Fine examples of architectural art are the engravings at Cerro Sechín in

northern Peru. Also the zoomorphic

images made up by small stone blocks built in into the stone terraces at

Choquequirao, an archaeological complex west of the city of Cusco, Peru, must

be regarded as architectural art and not as rock art, despite the unwanted

manipulation of the definition of rock art by Echevarría López &

Valencia García and despite the

uncritical acceptance of their paper in Rock Art Research (2009: 213). On the

other hand, rock art is the corpus of imagery (mainly petroglyphs and

rock paintings) that is found on natural rock surfaces (boulders and outcrop).

In the Andes of

South America it is not uncommon to find true rock art very near prehistoric structures,

but in relation with the hundreds of rock art sites in the Andes those

instances must be regarded to be erratic. Some rock art sites are only very

close to ancient structures, like the group of petroglyph boulders at Quebrada

de San Juan, Virú, northern Peru. In some cases petroglyph boulders are found

distributed among the ruins of ancient structures, like at Tomabal in northern

Peru (Van Hoek 2007) and at Rincón del Toro, La Rioja, Argentina (Van Hoek

2011). Some boulders at those sites (only?) seem to be part of the ruined walls. In other cases petroglyph boulders definitely form part of the ancient

structures, like at El Tambo in the Quebrada de la Guitarra in the Moche

drainage, northern Peru. Also in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile several sites feature decorated rocks that are part of

prehistoric structures, for instance the settlements of Tarapacá Viejo,

Camiña and Jamajuga (Vilches & Cabello 2006; Uribe 2006),

Vinto, Millune and Achuyo (Valenzuela,

Santoro & Romero 2004), and Suca (Sepúlveda, Romero & Briones 2005). Possibly three petroglyph

boulders originally were once associated with the structures of the ‘Pucará’ at San Lorenzo (AZ-11) in the

Azapa Valley of northern Chile. These boulders are now located at the Museo Arqueológico San Miguel de Azapa opposite

the “Pucará’ (Briones & Varela

2006).

Although there

are instances where true rock art has

been executed on the walls of ancient buildings (long) after the construction, for instance in Egypt (Van Hoek 2009), in

most cases the Andean examples most likely represent situations were petroglyph

boulders already occurred at the site (most evident at Tarapacá Viejo) and were

primarily and conveniently used as building material at the time of construction. This however does not rule out the

possibility that the ancient images were still venerated at and after the time of construction and

therefore they were so placed that they remained visible. Yet, this may also

have been done purely because of decorative motives.

I now argue that

in every single case in which a boulder

with rock art forms part of a prehistoric construction it should be ascertained

if that boulder has been used solely for building purposes or not. In most

cases those decorated boulders in ancient walls form the base of that wall, which argues in favour of being used as building

material. Unfortunately, many structures are too derelict and too much

disturbed to ascertain the original position of the decorated boulders. Also,

many of such boulders are rather large and will have readily been discarded as

building material. For instance, at Jamajuga in the Quebrada de Mamiña, Chile, several

boulders with petroglyphs are rather large and occur on a steep slope (contrary to for instance Tarapacá Viejo) among a large

number of boulders (Trincado 2009). Apparently it was not feasible to use them,

at least, not to move them. Therefore, another possibility is that (especially large)

boulders were left in situ, while the

construction was built around it. Also this possibility should be investigated

in every single case.

However, we have

to accept the fact that in most cases it will remain obscure if the occurrence

of a decorated boulder in an ancient construction has been intended to

represent architectural art or not. The incorporation of decorated rocks may

easily have been a matter of convenience. If so, the images on the boulders will

represent true petroglyphs. However, the following example might represent an instance in which architectural art has been incorporated on purpose into a prehistoric building. It concerns two boulders in

the prehistoric village (aldea) of

Ramaditas in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. In this paper I will describe

and discuss those two boulders and simultaneously will attempt to answer the

question: Aldea de Ramaditas:

architectural art or rock art?

Aldea de Ramaditas

The Atacama

Desert of northern Chile features a large number of most interesting rock art

sites. On the way to Tamentica, an important rock art site in the Quebrada de

Guatacondo (also referred to as Huatacondo),

our guide not only pointed out several geoglyphs in the Quebrada but also drew

our attention to the site of a very ancient village called Aldea de Ramaditas.

Knowing of our interest in rock art, he disclosed that there was ‘rock art’ in

this settlement as well.

It proves that

the Ramaditas site has been excavated. On the internet I found references to three

publications about Ramaditas; two by Mario Rivera (2002 and 2005) and one by

Rivera, Shea, Carevic & Graffam (1995-1996), but it is unknown to me if the

rock art has been reported in those publications. However, I was much pleased

that Rolando Ajata López, archaeologist at the Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, Chile, helped me out by sending me

an unpublished report about the rock art of the Guatacondo Valley (Cabello

& Ajata 2010). The surveys by Gloria Cabello & Rolando Ajata offer

valuable information, especially about Ramaditas and nearby Tamentica. Some of this

information has been used by me in this paper. Because the following details about

the Ramaditas site will be largely unknown to many rock art researchers, I

present a brief description of the Ramaditas site and a more comprehensive discussion

of its ‘rock art’.

The following

information has been obtained from a review of the 2002 book by Mario Rivera: Ramaditas is a Late-Formative

village-farming site in the Quebrada de Guatacondo. In many ways, Ramaditas and

the group of sites in the Guatacondo archaeological district are unique because

of excellent preservation of architectural features, the presence of a vast

network of irrigation canals and agriculture fields, fabric, basketry, and

macro-botanical remains. The settlement area -including structures and

agricultural fields- has been estimated in approximately 600 hectares.

Radiocarbon age determinations place occupation at this site within the Alto

Ramirez II Phase, between 2,500-2,000 years B. P., a time span when large

village-farming communities first appear in this sector of the Andes. Indeed,

Ramaditas represented one of the earliest occupations in the Guatacondo

District, a series of six roughly contemporaneous village-farming sites and

associated structures arranged along the present-day Guatacondo gully (Baied 2007).

Because of the

drifting sands, much of the site is now covered up again. However, what is

visible today (2011) is still impressive and interesting. The site is located

at an altitude of about 1150 m O.D. and is roughly 80 km inland. The low ruins

are barely visible from the dirt road to Tamentica and therefore easily missed.

The settlement is situated on a vast plain cut by the Quebrada de Guatacondo.

At this point however, the Quebrada does not form a valley but forms a shallow

gully of about 2 m deep. At this point the gully is called Quebrada de

Guatacondo, while further upstream and east of Cerro Challocollito the gully

becomes more and more a valley. This stretch between Cerro Challocollito and

Tamentica is sometimes called Quebrada de los Pintados, although Cabello &

Ajata (2010: Plano 1) mention a (different?) Quebrada de Pintados further south.

About 5 km to the north of the village ruins the isolated group of hills called

Cerro Challacollo (1573 m. O.D.) is clearly visible.

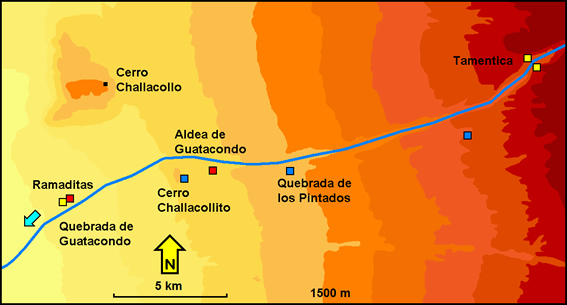

Figure

1. Map of the surveyed area (100 m contour-interval). Drawing by Maarten van

Hoek

(based on the map by Clarkson,

Johnson, Johnson, Briones & Johnson 1999: 21).

There are other important

archaeological remains in this area (Figure 1). About 9 km to the east of

Ramaditas is another ancient settlement (red square in Figure 1) called Aldea

de Guatacondo. On the eastern slopes of Cerro Challocollito (6.5 km east of

Ramaditas) is a small group of geoglyphs (blue square), while 13 km east in the

Quebrada de los Pintados are a few geoglyphs on a north facing ridge that overlooks

the Guatacondo valley. They are rather easily visible from below. The most

important group of geoglyphs however occurs at about 18 km east of Ramaditas. These

geoglyphs are invisible from Guatacondo valley floor as they are located about

1400 m south of the valley and about 100 m higher. They also appear on a north

facing ridge and overlook an ancient north-south road. More groups of geoglyphs

are found along this route. Importantly, 20 km ENE of Ramaditas is the well

known petroglyph site (yellow squares) of Tamentica that will be discussed

further on. East of Tamentica are several other rock art sites (rock paintings

and petroglyphs) that have been studied in detail by Gloria Cabello & Rolando

Ajata (2010). However, none of the images at these sites show definite parallels

to the Ramaditas imagery.

The plain on

which Ramaditas is situated only very slightly slopes to the SW. The area

around the settlement consists of sands and fine gravel, while at certain places

concentrations of somewhat larger boulders (of uniform rock type) occur. Directly

to the W and SW of the village is an area where agricultural fields with irrigation

systems are still visible. These fields also exist at many other parts of this

vast plain, especially to the NE of Ramaditas, where also low, circular

structures are visible. The village itself comprises a number of circular/oval houses

that are clustered together (like nearby Aldea de Guatacondo and more distant Tulor

near San Pedro de Atacama) and a number of isolated houses (Ajata 2010).

Many of the walls have been reduced to low, circular ridges in the sand. The

walls that are still standing are up to two metres high and originally would

have been capped bay a construction of reed (rama). A reconstructed model-house of such a dwelling can be

visited at Tulor, south of San Pedro de Atacama. Some of this reed is still

lying around, for example in the isolated house with the ‘rock art’. The wood

to support these roofs came from a nearby forest, now completely disappeared,

but several pieces of wood are still lying scattered around. The walls have

been made by adobe bricks (Figure 2) and/or by cementing together fairly large

boulders with clay from the riverbed. These boulders are of various types of

stone and most are rounded (water-worn). They probably have been collected from

a nearby source of river cobbles. Several house ruins still show door openings,

small windows and even a stair.

Figure

2. One of the houses at Ramaditas, Chile.

Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Interestingly, the

walls of the dwellings contain several types of anthropic markings. First, at

least one section of a wall clearly displays finger flutings (acanalado

por dedos). Flutings are lines that human fingers leave when drawn

over a soggy surface, like wet clay. Although they form groups of parallel

lines, these markings probably have no specific meaning and represent no form

of ‘rock’ art but simply indicate that the clay that people used to cement the

cobles together had been applied with their fingers (Figure 3). They may have

been left there because of a decorative aspect, although it is even possible

that they appear on a section of the wall that has been repaired (possibly even

in very recent times).

Figure

3. The ‘finger flutings’ at Ramaditas, Chile.

Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure

4. Some of the ‘finger holes’ at Ramaditas, Chile.

Photograph by Maarten van

Hoek.

Several other

sections of walls show small holes made by people who have poked holes into the

clay with their fingers (Figure 4). The holes thus created show no pattern and

may possibly have been made just for fun. However, Cabello & Ajata suggest

that some of them may represent simple ‘faces’ (2010: 5). Also a few figurative

markings in the clay have been reported by Cabello & Ajata (2010: 5 - see Lámina 2:D, 2:F, 2:G and 2:H), as well

as two stones with traces of paint (2010: 6 - see Lámina 3:C and 3:D). The last type of anthropic markings concerns the

two ‘petroglyph’ stones that will be discussed now.

Ramaditas’ ‘Rock Art’

The two boulders with ‘petroglyphs’ have

been cemented in into the inner wall of the northern arc of an isolated house

(Figure 5), labelled Recinto 17 by

Cabello & Ajata (2010: Plano 2). Recinto 17 is situated only a short

distance to the W and SW of the two main clusters of houses. The larger Boulder

(1) is found between the door opening and a small window; the smaller Boulder (2)

forms the right hand ‘post’ of that small window (Figure 6). Importantly, both

Boulders are not placed at the base

of the wall.

Figure

5. The north wall of Recinto 17 at

Ramaditas, Chile. In the background is Cerro Challacollo.

Photograph by Maarten

van Hoek.

Figure

6. The north wall showing the two decorated boulders at Recinto 17 at Ramaditas, Chile. Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Boulder 1: The larger boulder is of a yellowish-pink colour and is now found

about 15 cm above present day soil level (base of the stone to ground level),

although in reality the distance would have been greater since the room has

partially been filled up with drift sand. The visible part of its surface

measures 33 cm in height by 44 cm in width. On its vertically oriented surface

are three petroglyphs (Figures 7 and 8). There are two fully pecked, laterally

depicted zoomorphs, each showing four legs and ears. Both look to the right

(for the observer). The left-hand zoomorph is about 8 cm in length and has a tail

that is pointing upwards while it seems to show an open mouth. However, the

lower jaw could also represent a short rope attached to the anthropomorph. The

right-hand zoomorph measures 9 cm in length and has a tail that curves

downwards. It seems to have an open mouth, but not as clearly as the other

zoomorph. These two zoomorphs probably represent images of camelids.

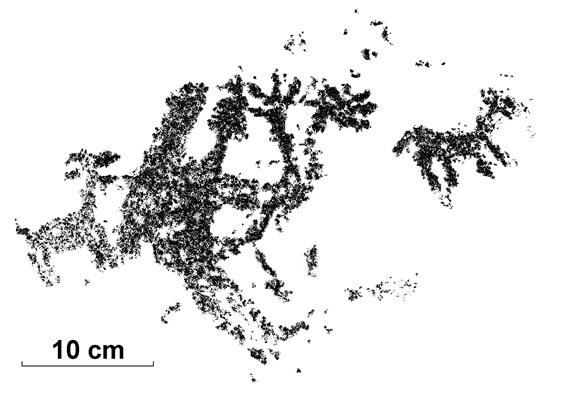

Figure

7. Boulder 1 at Recinto 17 at

Ramaditas, Chile.

Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure

8. Drawing of the images on Boulder 1 at Ramaditas, Chile.

Drawing

by Maarten van Hoek.

In between the two zoomorphs is a

petroglyph of an anthropomorph, again depicted in profile and also looking to

the right (for the observer). Also this figure has been fully pecked

(disregarding small and randomly distributed un-pecked areas). The

anthropomorph is 22 cm in height and measures 16 across. Several features are

interesting. First of all the anthropomorph seems to carry something on its

back, which may indicate that he is a traveller (backpacker). The anthropomorph

has a rather long neck and a small head with a short appendage from the top.

There are no facial features. It has also two legs and two arms that clearly

show splayed fingers. One hand may have four fingers; the other may have six (in

analogy with the pair of feet on panel OFA-01-02 at Ofragía, Chile: the left

foot has six toes, while the right foot has only four toes).

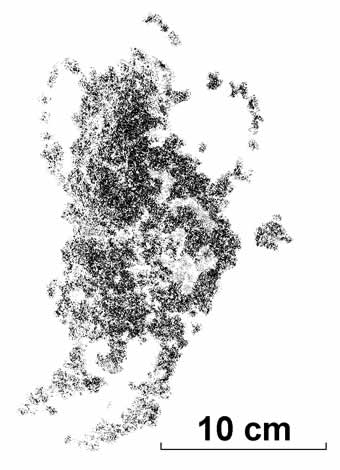

Boulder 2: At about 55 cm to the right of Boulder 1 is the second boulder of

similar colour, which forms part of a small window. The base of the stone is

about 50 cm above present day soil level and measures 29 cm in height by 28 cm

in width. It features only two petroglyphs, both less clearly and very

superficially pecked (Figures 9 and 10). The most obvious petroglyph certainly

represents a biomorphic figure and probably is an anthropomorph. It measures 22

cm in height. It cannot be determined with certainty whether the figure is intended

to be observed laterally or frontally, although the position of the two short legs

suggests that the figure has been depicted to be viewed frontally. In between

the legs is a short, downward pointing appendage. This might indicate male gender. The ‘head’ is directly attached to the

body; there is no neck. The ‘head’ is a large circular pecked area showing no

facial details. Emerging from the shoulder areas are two curved lines of dots

that might represent the ‘arms’. The

body is almost fully pecked, but an area to the right of the main body mass may

represent something else (an arm?, a backpack?, a spiral-like appendage?). The

other marking on this boulder is a small, circular pecked area to the right of

the biomorph.

Figure

9. Boulder 2 at Recinto 17 at

Ramaditas, Chile.

Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure

10. Drawing of the image(s) on Boulder 2 at Ramaditas, Chile.

Drawing

by Maarten van Hoek.

Interpretation

The biomorph on Boulder 2 is too

amorphous to be interpreted with any certainty. The anthropomorph on Boulder 1 together

with the two zoomorphs may depict a scene in which a specific person

accompanies two animals into a certain direction (into his house?). Such a

person may have been a shaman or a pochteca,

an Andean traveller/trader who is often carrying a backpack and other

paraphernalia, like a flute (Van Hoek 2005: 28). Interestingly, the curved arms

and the empty hands are placed in a very specific position, reminiscent of many

other petroglyphs in the Desert Andes where biomorphs (anthropomorphs and zoomorphs) are ‘playing a wind

instrument’. Several of the aforementioned biomorphs in such a specific

position do not hold a ‘wind

instrument’. Their hands are completely empty, like the splayed hands of the

enormous ‘monkey’ geoglyph on the Nasca Pampa in Peru. I have suggested earlier

that these ‘empty-handed’ biomorphs may hold an ‘invisible’ object, like a

flute (Van Hoek 2005). This might be

true for the anthropomorph on Boulder 1 as well.

Interestingly, there is also a groove

that unites the genital area of the anthropomorph with his arms. This groove might represent an erect phallus. It is now

generally accepted that the Andean flute may only be played by males (Van Hoek

2005: 26) and indeed several (but definitely not all) petroglyphs of ‘flute players’ in the

Desert Andes show some indication of male gender (Van Hoek 2005: Fig. 6). Interestingly,

there are many petroglyphs in the Southwest of the United States where

‘flute-player’ petroglyphs have an (erect) phallus (as well as being ‘humpbacked’).

Two examples, both almost analogous to the Ramaditas figure on Boulder 1, are

found in the Galisteo Basin, New Mexico, USA (Slifer 2000: Plate 20) and at the

enormous Three Rivers site, also in New Mexico (Van Hoek 2010: Fig. 18.11). These

petroglyphs are found no less than 7330 km NW of Ramaditas and although a direct cultural relationship is

impossible, the distant figures still may share a similar symbolism. If we

accept that also the biomorph on Boulder 2 represents a male, we might conclude that this specific house

at Ramaditas had been inhabited by a male (gendered?) person. It might even be the dwelling of the shaman

of this village.

Dating the ramaditas ‘petroglyphs’

In the Introduction it became clear

that Ramaditas is one of the earliest occupation sites in the Guatacondo

District. The complex probably dates from 500 B.C. to A.D. 0., the era when

large village-farming communities first appear in this sector of the Andes. However,

Cabello & Ajata (2010) refer to the work of Rivera, Shea, Carevic &

Graffam (1995-1996) and mention a date of 90 B.C.. There now are four

possibilities regarding the dating of the Ramaditas ‘petroglyphs’.

1). The first option is that the two

petroglyph boulders were found locally and - together with many other (undecorated)

boulders - were used to construct the walls of Recinto 17. In this scenario, these boulders had already been

decorated with images (long?) before the village was founded. Thus the images

would be older than the construction of the village and initially they would have

been true petroglyphs. The boulders were incorporated into the wall in such a

way that the images remained visible. This may have been done for decorative

reasons, but it is more likely that the imagery was important to the person(s)

residing in this dwelling. Their specific positions a short distance above

ground level seems to point to intent. In this case rock art may have been turned into architectural art.

2). A second option is that the

images were made when the village already existed. The manufacture of the

images may have been done in the field, at the spot where they were found, or

the boulders were first transported to the village, decorated there and

subsequently built into the wall. In this case there is ‘only’ question of architectural art.

3). The third option is that a

person who inhabited the dwelling (or someone else) made these images as signs

of his (or her?) function after they

were fixed into the wall. Especially Boulder 1 is large enough and firmly fixed

into the wall to receive the blows of a stone implement. However, the position

of Boulder 2 is much less fixed and this may confirm the idea that the

boulder(s?) was (were) already decorated (which seems to confirm option 1 or

option 2). Also in this case the images represent architectural art rather than rock art and would probably date from

500 B.C. to A.D. 0.

4). A fourth option departs from the

idea that the images were made after the abandonment of the village. The houses were empty and travellers might have

used the ruins as temporary shelters. Someone may have executed these images on

those two boulders during such a stay. Again, the rather unstable position of

Boulder 2 argues against this idea. In this case the images may be regarded as rock art and could date from any time

from A.D. 0 to the Spanish Invasion.

From these four options it proves

that the occurrence of a ‘petroglyph’ boulder built into a dateable structure

provides no indication of the age of the imagery,

as the images at Ramaditas do not occur in a sealed context. Importantly,

parts of the clay (especially a small part with two finger-holes) still cover

Boulder 1, while other parts (that once might have covered a portion or all of the ‘petroglyphs’) may have fallen off.

Unfortunately it cannot be ascertained to date if indeed the clay once covered

(part of or all of) the ‘petroglyphs’ of Boulder 1. If the clay once covered

the whole scene (which, because of its slightly domed surface, is unlikely), it

would indicate that the builders only used the boulder and did not have the intention to (re)sanctify its imagery.

However, it would have been quite impossible to completely cover Boulder 2 with

clay, being a corner-stone of a small window.

Another interesting fact is that the

surfaces of the boulders visible today and their images hardly seem to have been patinated. This may indicate that the

petroglyphs were manufactured not that long before (option 1) or during (option

2) the construction of the village. After being incorporated into the wall of

the house they became protected from the sun, even when the site was abandoned.

The now vertically placed surfaces of the two boulders notably face south and

only at the peak of the summer they will catch some sun light, but never

perpendicularly (because of the position of the site on the Southern Hemisphere:

21º S and only 268 km north of the Tropic of Capricorn).

Graphical context

Unfortunately, the graphical content

of only two boulders offers too small a basis to definitely link these

‘petroglyphs’ with other graphical representations in the direct neighbourhood or

indeed in a much wider area. The two small ‘camelids’ show no specific detail

or style and can be of any prehistoric date. Similar representations of

‘camelids’ occur at many places in the Desert Andes. Also the rather amorphous ‘biomorph’

on Boulder 2 shows no specific features.

Only the anthropomorph on Boulder 1

could be used for comparison. Fortunately, Ramaditas is located at the western

fringe of an area that is rich in rock art and also has a number of geoglyph

sites (see Figure 1). However, none of the anthropomorphic figures of the

geoglyphs known to me has any resemblance with the anthropomorph on Boulder 1. Most

distinguishing are the ‘backpack’, the possible phallus and the specific

position of the arms and hands. Although there are several rock art sites further

east in the Quebrada de Guatacondo (Cabello & Ajata 2010) only the

graphical content of the site of Tamentica-1 proved to be useful to compare the

Ramaditas anthropomorph with.

Tamentica-1

Tamentica-1 (the site at the north side of the bottleneck in the

Guatacondo Valley) no doubt once was a very important rock art site and it still is. However, I was shocked

to see how violated this sacred site was at time of our visit. Many stones were

displaced, badly disturbed and severely damaged. Another disappointment was

that the newly built Site Museum was closed and - because it was said that vandals

stole many items from the museum - it probably will remain closed.

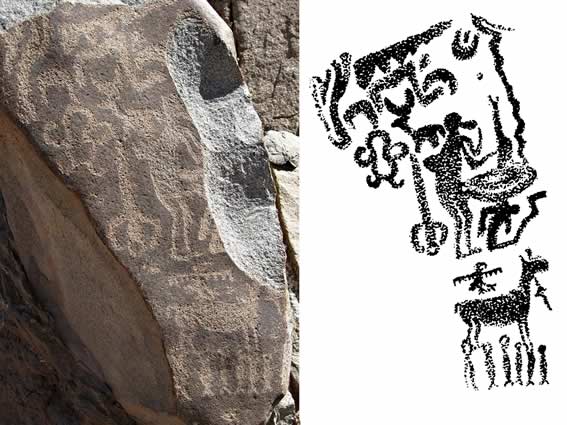

Fortunately, many of the petroglyphs

are still visible. Among these are several fully pecked ‘camelids’, more or

less of the same type as seen on Boulder 1 at Ramaditas. There are also many

anthropomorphic figures, and what is more important, several of those figures

proved to have a ‘load on their backs’ (or simply are ‘humpbacked’). Especially

this ‘backpacker’ theme links Tamentica with Ramaditas. However, this parallel

offers no conclusive proof that the Tamentica manufacturers are also

responsible for the imagery at Ramaditas. Notably, petroglyphs of ‘backpackers’

occur at several rock art sites in the Desert Andes (for instance at Ariquilda

in the Quebrada de Aroma and at Calaunza in the Codpa Valley of Chile and at Miculla

and Huancor in Peru). However,

Tamentica seems to be the site with the biggest number of such ‘backpacker’

figures. Moreover, several anthropomorphic figures at Tamentica have their arms

in unusual positions. One such figure is more or less in the same position as

the anthropomorph on Boulder 1, but it has no hands. Unfortunately this cannot

be checked anymore as this specific boulder has severely been damaged (Figure

11). A complete drawing of this panel appears in the book by Grete Mostny

Glaser & Hans Niemeyer Fernández (1983: Fig. 45). Also this anthropomorph

is associated with a small, pecked ‘camelid’.

Figure 11. Damaged boulder at Tamentica-1,

Chile. Photograph by Maarten van Hoek.

Drawing by Grete Mostny Glaser &

Hans Niemeyer Fernández (1983: Fig. 45).

Several ‘backpackers’ at Tamentica

seem to hold object (staffs?), while a few panels show scenes involving

‘backpackers’, walking in a row (as on Bloque 32 - Panel I), or even when standing in a raft. At least one ‘backpacker’ at

Tamentica (on Bloque 7 - Panel D) seems

to be phallic and has a load on its

back that is similar in shape to the load on Boulder 1 (Figure 12). On Bloque 40 are two profile figures in a

row that seem to ‘play a wind instrument’ and one of them seems to carry a

‘backpack’. Remarkably, none of the anthropomorphs that I inspected at

Tamentica-1 clearly displays (splayed) hands (like the anthropomorph on Boulder

1). It is certain that the petroglyphs at Tamentica date from different

periods. For example, the many raft-petroglyphs are said to date from the Arica

Culture (A.D. 1000 to A.D. 1500) (Mostny Glaser & Niemeyer Fernández 1983:123),

but other images are said to date from around B.C. 100 to A.D. 100 (Mostny

Glaser & Niemeyer Fernández 1983).

Figure 12. Detail of a boulder at

Tamentica-1, Chile, showing three ‘backpackers’.

Photograph by Maarten van

Hoek.

Conclusions

What are the facts in this story?

First of all, it is certain that the village of Ramaditas is one of the oldest agrarian

settlements in the Atacama Desert. Its foundation probably dates around 500

B.C.. The second fact is that two boulders - incorporated into the northern

wall of an isolated house at Ramaditas - bear pecked images of altogether four

biomorphs. A third fact is that further east several expressions of prehistoric

art are found (geoglyphs and rock art) and that especially the rock art

repertoire of Tamentica has certain elements in common with the anthropomorph

on Boulder 1 at Ramaditas. The rest of the story involves hypotheses only.

It is also a fact that we do not know what the Ramaditas images stand

for. It is possible however - because of the ‘backpack’ - that the

anthropomorph on Boulder 1 represents a Pochecta,

an Andean merchant-traveller. In addition to this suggestion it is possible

that - because of the phallus and the position of the hands - the figure

represents ‘a shaman who is playing an invisible flute’. The presence of

‘backpackers’ and ‘flute players’ at the rock art site of Tamentica-1 seems to

confirm the hypotheses postulated in this survey. A plausible theory (but still

a theory) would be that Recinto 17

belonged to a (travelling?) shaman and that his function was symbolised by the

imagery in his or her house.

It is also a fact that we do not

know exactly when the four

‘petroglyphs’ were made (especially petroglyphs are notoriously difficult to

date). In this respect I explored four options. However, it is very likely that

the images date from around 500 B.C. (if we accept 500 B.C. as roughly the date

that the house was built). Unfortunately, it is - in general - too easily

accepted that also the rock art in the vicinity of or incorporated in

prehistoric structures has been manufactured by the builders/occupants of those

structures. However, it is not at all certain if indeed the residents of those

settlements were also the manufacturers of the imagery on the rocks; it is possible

but indecisive. This uncertainty also applies to the built-in images at

Ramaditas.

There are several other sites in the

Atacama Desert where rock art is found directly associated with a settlement. I

mentioned Tarapacá Viejo, Camiña, Jamajuga, Vinto, Millune, Achuyo, Suca and

San Lorenzo. However, in those cases none of the decorated rocks has been incorporated into a house in the same way as at Ramaditas. Despite this distinctive

difference, however, the key question remains unsolved. Were the Ramaditas images

once true petroglyphs, or have they been made to serve as architectural art,

i.e. have they been made exclusively to be incorporated into the wall of Recinto 17? We will probably never know.

Acknowledgements

I am most

grateful to Rolando Ajata López who provided me with much useful information

about Chilean archaeology, including an unpublished report on the rock art of the

Guatacondo Valley of northern Chile. Rolando Ajata López has also been so kind to read and comment on the

draft text, but of course the contents of this paper are completely my

responsibility. We are also indebted to our guide who expertly showed us the

rock art site of Tamentica and who took us to the ‘petroglyphs’ at Aldea de

Ramaditas. I also thank my wife Elles for her assistance during our surveys in Guatacondo.

—¿Preguntas,

comentarios? escriba a: rupestreweb@yahoogroups.com—

Cómo

citar este artículo:

van Hoek, Maarten. Aldea de Ramaditas, Chile: Architectural Art or Rock Art?

En Rupestreweb, http://www.rupestreweb.info/aldearamaditas.html

2011

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ajata L., R. 2010. Plano de Aldea Ramaditas, Quebrada de Huatacondo. In: PicasaWeb: https://picasaweb.google.com/rolandoajata/Mapas#5449418000125616658

Baied, C. A. 2007. Chungara.

Vol. 39-1. pp 135-136. Revista de Antropología Chilena.

http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=s0717-73562007000100009&script=sci_arttext

Briones M. G. L.

& R. Ajata L. 2004. Video Documental elaborado en el Proyecto Arqueologico "Puesta en

Valor y Protección del Yacimiento Arqueológico de Tamentica". In YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PkV6Pufc3Q&feature=related

Cabello, G. & R. Ajata. 2010. Revisitando el arte rupestre

de Huatacondo. Informe año II. Unpublished

Project Paper. Proyecto FONDECYT -

1080458.

Clarkson, P. B., G. Johnson, W. Johnson, L. Briones & E. Johnson. 1999. Low-cost high-return

aerial photography in archaeology. Inora, Vol. 24. pp 21-25.

Echevarría López, G. T. & Z. Valencia

García. 2009. The ‘llamas’ from Choquequirao:

a 15th-Century Cusco Imperial rock art. Rock

Art Research. Vol. 26-2. pp 213-223. Melbourne.

Briones M, L. &

R. Varela G. 2006. Museo Arqueológico San Miguel de Azapa: Expociones. Universidad de

Tarpacá. http://www.uta.cl/masma/expos/index.htm

Mostny Glaser, G.

& H. Niemeyer Fernández. 1983. Arte Rupestre

Chileno. Serie El Patrimonio Cultural Chileno. Colección Historia del Arte

Chileno. Publicación del Departamento de Extensión Cultural del Ministerio de

Educación.

Rivera, M. A. 2002. Historias del Desierto: Arqueología del Norte de Chile. Editorial

del Norte, La Serena, Chile.

Rivera, M. A. 2005. Arqueología del Desierto

de Atacama. La etapa Formativa en el Área de Ramaditas/Guatacondo. Santiago de Chile: Universidad Bolivariana

(Colección Estudios Regionales y Locales).

Rivera, M., D. Shea, A., Carevic & G.

Graffam. 1995-1996. En torno a los orígenes de las sociedades complejas andinas: excavaciones en

Ramaditas, una aldea Formativa del desierto de Atacama, Chile. Diálogo Andino. Vol. 14/15: 205-239.

Arica.

Sepúlveda, R. M.

A., Á. L. Romero Guevara & L. Briones. 2005. Tráfico de caravanas, arte rupestre

y ritualidad en la Quebrada de Suca (extremo norte de Chile). Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena. Vol. 37-2. pp 225-243.

Slifer, D. 2000. The serpent and the sacred fire. Fertility images in Southwest rock art.

Museum of New Mexico Press, NM.

Trincado, P. 2008. http://www.flickr.com/search/?w=all&q=Jamajuga+&m=text

Uribe, R. M. 2006. Acerca de complejidad, desigualidad

social y complejo cultural Pica-Tarapacá en los Andes Centro-Sur (100-1450

dC). Estudios Atacameños. Vol 31, pp

91-114. Universidad Catolica del Norte, San Pedro de Atacaman, Chile.

Valenzuela, D., M. C. Santoro & Á. Romero. 2004. Arte rupestre en

asentiamentos del Período Tardío en los valles de Lluta y Azapa, Norte de

Chile. Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena. Vol. 36, Nº 2, 2004. pp 421-437.

Van Hoek, M. 2005. Biomorphs

‘playing a wind instrument’ in Andean rock art. Rock Art research. 22-1, pp 23-34. Melbourne, Australia.

Van Hoek, M 2007. Petroglifos Chavinoides cerca de

Tomabal, Valle de Virú, Perú. Boletín de

SIARB, Vol. 21, pp 76-88. La Paz, Bolivia.

Van Hoek, M 2009. Egyptian temple petroglyphs. SAHARA.

Vol. 20. pp 171-176. Milano, Italia.

Van Hoek, M 2010. Mogollon Rock Art and the Status of the ‘Flute

Player’. In: Proceedings of the XV World

Congress UISPP. Lisbon. BAR International Series, pp 161-173, Archaeopress;

Publishers of British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, England.

Van Hoek, M. 2011. Banda Florida. An overview of a rock art site in La Rioja,

Argentina. In: Rupestreweb. http://www.rupestreweb.info/bandaflorida.html

Vilches, F. & G.

Cabello. 2006. “De lo público a lo privado: el arte

rupestre asociado al complejo Pica-Tarapacá”. Actas del V Congreso Chileno de Antropología, San Felipe 2004.

[Rupestreweb Inicio] [Introducción] [Artículos]

[Noticias] [Mapa] [Investigadores] [Publique] |